The decision of the European Union to finance Ukraine through joint borrowing is causing concern in the markets, analysts said on Friday 19 December.

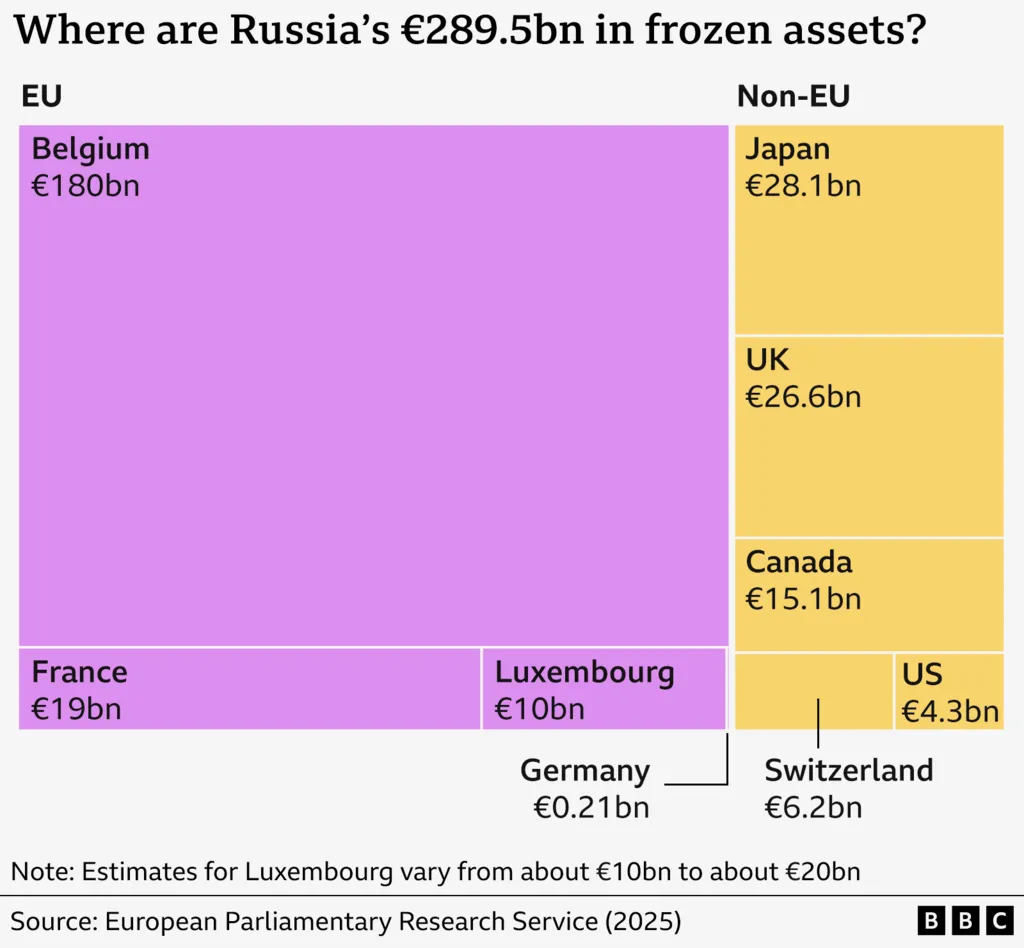

With this decision, the use of common debt as a financing solution is being entrenched, while at the same time a legally controversial plan to utilize Russian assets is being avoided.

EU leaders agreed on Friday 19/12 to borrow funds in order to grant loans amounting to 90 billion euros (105 billion dollars) to Ukraine, to finance its defense against Russia over the next two years, leaving out Hungary, Slovakia, and Czechia.

Increased supply of euro debt

Investors in EU joint debt face the risk of increased supply in the coming years, as officials in Brussels seek to increase borrowing in order to finance Ukraine.

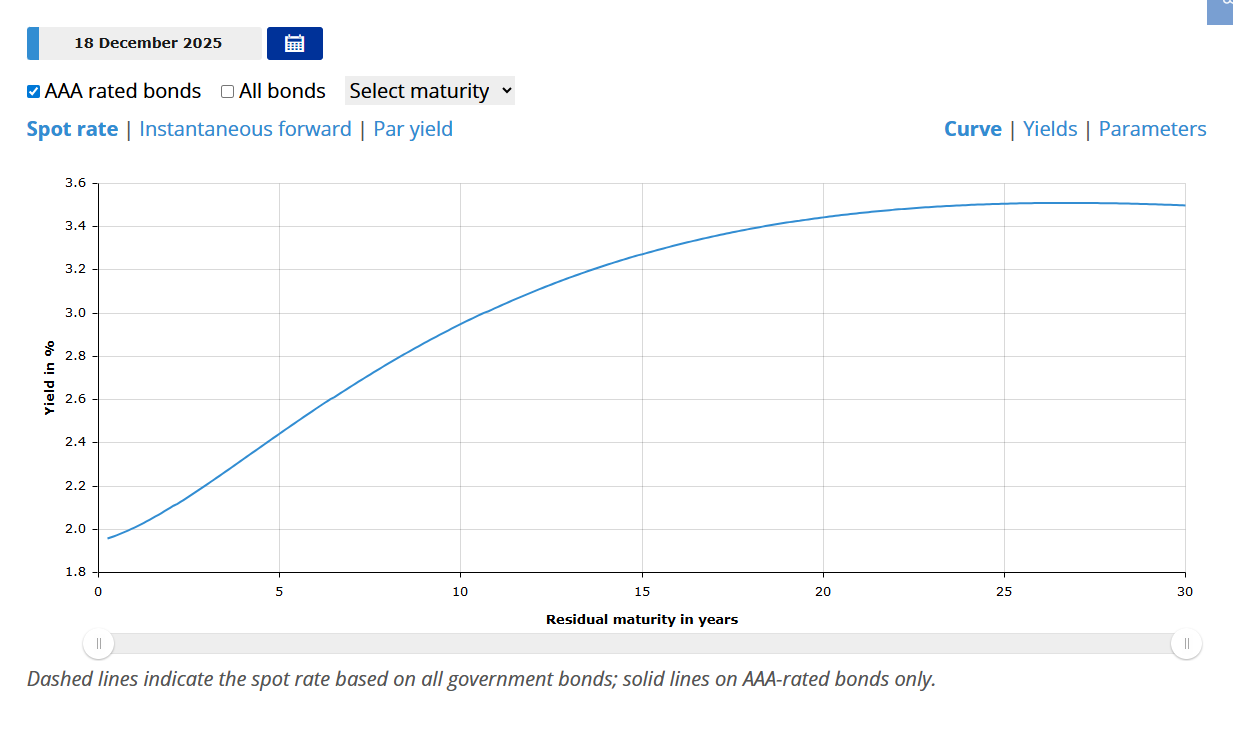

Yields on EU 30-year bonds rose by nine basis points to 4.14% on Friday (19/12), the largest increase among eurozone issuers.

This development follows a strong period of outperformance versus German debt, during which the EU borrowing premium narrowed from 85 basis points at the beginning of the year to 60 today.

Investors, according to analysts, have been attracted both by the improvement in the liquidity of EU bonds and by efforts to align the EU borrowing program with those of the member states.

However, it remains unclear how exactly the EU will raise additional capital from the markets if this becomes necessary, and this is causing pessimism regarding financial stability.

In a teleconference this week, EU officials told investors that they have the capacity to cover any additional financing needs for Ukraine through a wide range of tools, from short-term Treasury bills to bonds with maturities spanning decades.

The outperformance of EU bonds will be tested by the increased supply, said Christoph Rieger, head of rates and credit research at Commerzbank.

“We expect that any additional financing needs will initially be covered through increased issuance of Treasury bills.”

Ukraine will not have to repay the EU loan until Moscow pays compensation to Kyiv, while in the meantime the Russian assets will remain immobilized in the EU.

The plan for bond sales

The EU announced plans to sell bonds worth 90 billion euros in the first half of 2026, an amount equal to that of the previous year, with an “indicative” target of 160 billion euros for the whole of 2026.

However, the legal texts governing the Union’s joint borrowing allow for a maximum bond issuance of up to 200 billion euros within 2026, compared with a limit of 170 billion this year.

Correspondingly, the upper limit for Treasury bills was increased from 60 billion euros in 2025 to 100 billion euros.

Combined with the ability to raise capital through repurchase operations (repos), this provides multiple leverage for increasing borrowing while dramatically increasing the risk of a debt crisis.

The European Commission will update its borrowing program “once the details of the new financing are finalized through the relevant legislative procedures,” it said in a statement.

The Union will pursue any additional issuance in a prudent and market-friendly manner, utilizing the full range of available financing tools.

The impact of the increased supply of EU debt on markets is complex, given that the Union has evolved into a major bond issuer only in recent years.

It intensified issuance in 2020 to finance the response to the pandemic and now issues amounts that compete with those of the largest member states.

The EU as a permanent debt issuer

“On the one hand, increased supply weighs on EU bonds and could lead to a decline in their prices,” wrote a team of analysts at UniCredit.

“On the other hand, unlike most issuers, EU bonds could benefit from increased issuance activity, as greater supply enhances their liquidity and makes them more comparable to European sovereign bonds.”

Analysts at Commerzbank estimate that any increase in borrowing via Treasury bills for the loan to Ukraine will be refinanced with bonds once the net financing phase of the Next Generation EU program, the joint debt program for post-pandemic recovery, is completed at the end of 2026.

This will establish the EU as a permanent issuer for the coming years, they said, adding that the bank advises its clients to take advantage of any pressure on EU bonds due to uncertainty over supply to build long positions.

It is worth noting that Eurostat sounded the alarm in the previous period, with a letter to the European Commission warning of a potential debt crisis in France and Italy due to their participation in the 210 billion euro loan to Ukraine.

Eurostat explained in its letter that the financial guarantees underpinning the 210 billion euro loan, supported by frozen Russian assets in Belgium, will be classified in national accounts under European practices as contingent liabilities.

Does the German “nein” to joint borrowing no longer apply? – Expected political reactions

One long-term benefit of the agreement is that the new borrowing will strengthen the perception that EU joint borrowing is becoming a more permanent feature of the policymakers’ toolkit, according to analysts, a development generally supported by investors.

“Joint borrowing at EU level is no longer taboo,” said Andrew Kenningham, chief Europe economist at Capital Economics, even if Germany is likely to resist significant and regular increases.

The EU began large-scale borrowing during the COVID-19 pandemic, but Germany was particularly cautious about the idea of its further expansion, indicating that the pandemic program was an exception.

The Union has just over 700 billion euros in outstanding joint debt.

Although new borrowing for the pandemic fund is nearing its end, it decided earlier in 2025 to borrow 150 billion euros over the coming years to finance loans to member states for defense projects.

It is certain that additional borrowing for Ukraine will increase the risk to overall financial stability.

More debt to support Ukraine, even if the amount is relatively limited, underscores that policymakers may continue to resort to this tool whenever needed.

Common bonds as a dangerous tool

This will reassure markets that the bloc is willing to borrow jointly in the event of future shocks.

In the short term, however, there is also the danger: the plan means that markets will have to absorb more borrowing at a time when they are already facing historically high financing needs, as Germany increases spending.

“I don’t know if it is the best solution from a market perspective to add more supply to markets that are already concerned about debt sustainability,” said Craig Inches, head of rates and cash at Royal London Asset Management.

The eurozone debt oversupply

Investors are beginning to realize that a new joint European borrowing effort is becoming more likely, as the region rushes to increase defense spending.

The restrained reaction in bond markets, which usually react nervously to increased spending, as discussions on defense intensified this month, suggests that investors currently view the increase in borrowing as manageable, but the 90 billion euro loan increases the pressure.

At the end of last year, investors considered joint borrowing directly by the EU itself less likely.

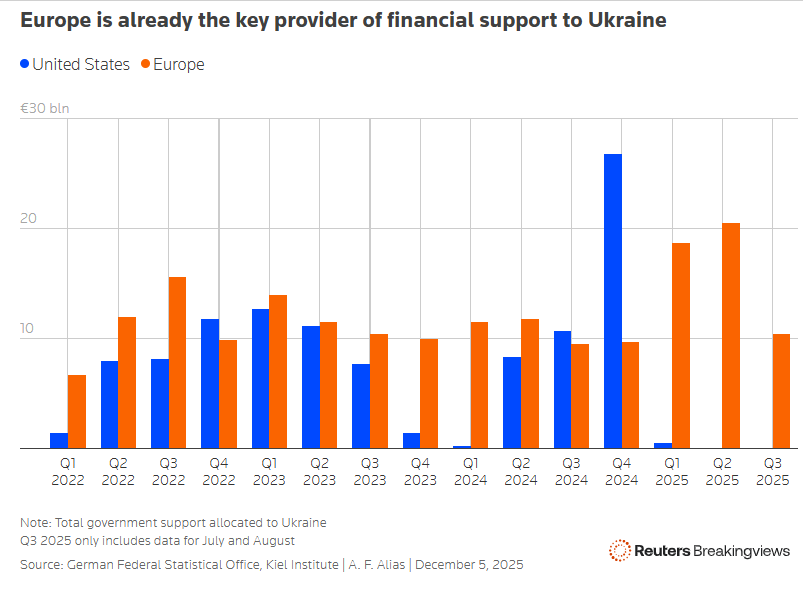

However, the need for action has returned, as United States – Russia talks on ending the war in Ukraine have de facto sidelined Europe and increased pressure on a bloc already urged by United States President Donald Trump to increase its spending.

The EU estimates that investments of 500 billion euros will be required over the next decade. However, increasing defense spending to 3% of GDP would require nearly 200 billion euros more annually.

Toward the issuance of defense bonds

“The instinctive reaction is that governments start to spend somewhat more, but it will not be huge amounts,” said David Zahn, head of European bonds at Franklin Templeton.

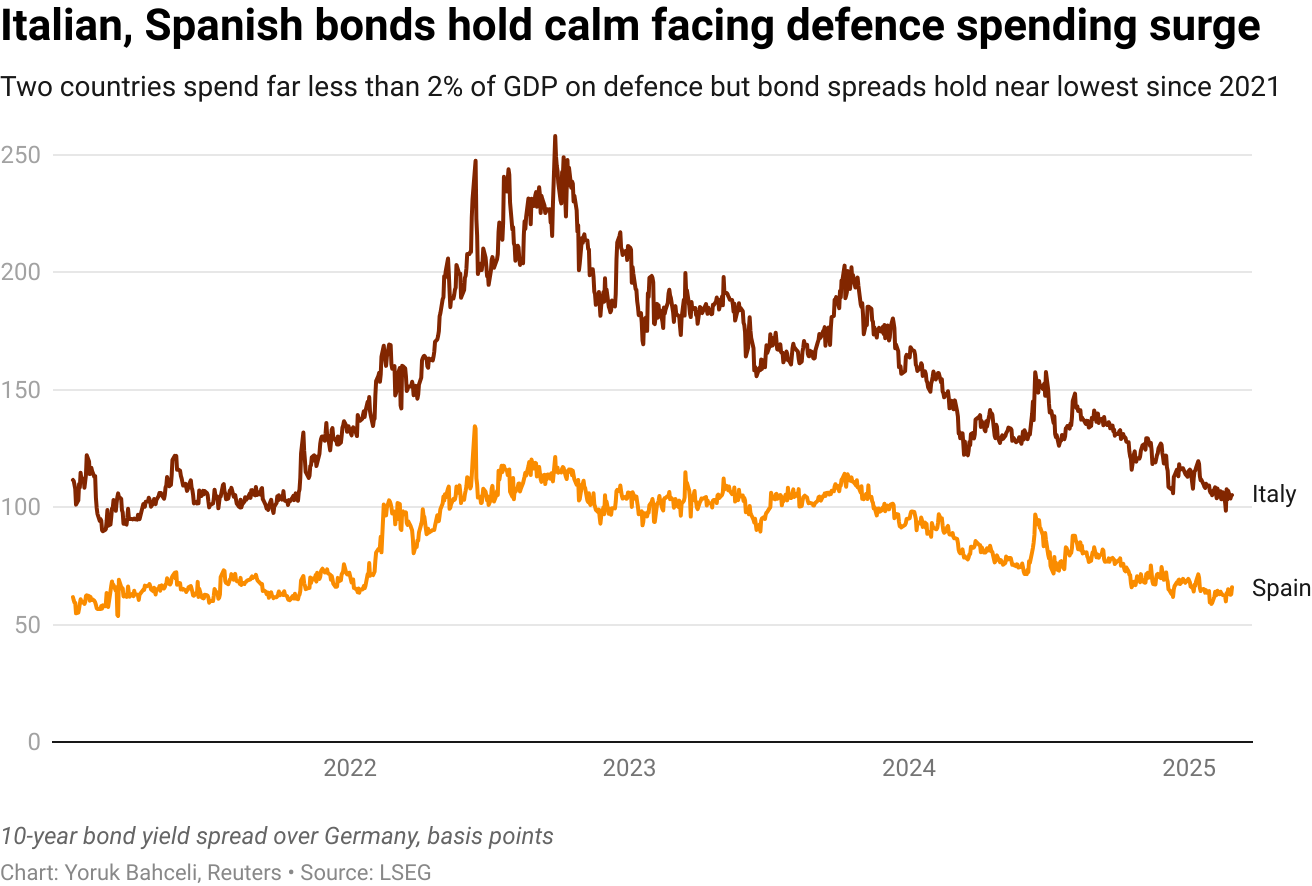

“The larger amounts will have to come from some form of centralized financing, because most budgets in Europe are relatively constrained,” he added, especially in Italy and France.

He himself has sold EU bonds, expecting more joint issuance, while Vanguard maintains a bet in favor of Italian and Spanish bonds.

“If policymakers are serious, then there will come a moment when we will have to think about issuing joint defense bonds,” said Nicolas Trindade, portfolio manager at AXA Investment Managers.

“That is where the greatest potential lies.”

Some analysts believe that even Germany, which would face a massive financing gap if it does not agree to a new defense fund, could benefit from the joint borrowing it has so far opposed.

Covering defense spending

Italy and Spain, which are already far behind a spending target that NATO is likely to raise sharply, have seen minimal changes in their sovereign bond markets, despite the increasing focus on strengthening European defense spending.

Whether it is a new financing vehicle that would also include Britain, or more EU bonds, the most welcome outcome for investors, as it would make the bloc a more permanent borrower, a common solution is expected, though not immediately.

Initially, the bloc is considering temporarily exempting defense spending from fiscal deficit rules.

Subsequently, it could transfer approximately 90 billion euros of unused loans from the Recovery Fund toward defense.

Thus, further joint borrowing may not emerge before 2027, said Apolline Menut, economist at Carmignac, adding that Germany’s efforts to find a rapid national solution could also reduce the sense of urgency.

The question is how much additional borrowing investors will tolerate, at a time when they are already purchasing historically high amounts of eurozone debt and are concerned about high deficits in major economies.

How much the loan to Ukraine will cost Europeans

EU taxpayers will have to pay approximately 3 billion euros annually in borrowing costs under a plan to increase joint debt aimed at financing Ukraine’s defense against Russia, according to senior European Commission officials, as reported by Politico.

The bloc’s leaders agreed in the early hours of Friday to raise 90 billion euros over the next two years, backed by the EU budget, to ensure that Kyiv’s war funds do not run dry in April.

The war-affected country faces a budget deficit of 71.7 billion euros next year and is in desperate need of capital to ensure its survival.

Many of the key features of the 210 billion euro financing package for Ukraine will be transferred to the new joint debt plan.

These include disbursements in tranches, safeguards against corruption, and a framework for how much money should be allocated to Kyiv’s military and to the country’s fiscal needs.

The new plan will provide Ukraine with 45 billion euros next year, offering Kyiv a critical lifeline as it enters the fifth year of hostilities. The remaining funds will be disbursed in 2027.

Annual interest at 3 billion euros for the loan

The new plan will not be cheap.

The EU is expected to pay around 3 billion euros annually in interest from 2028 onward, through its seven-year budget, which is largely funded by the governments of the member states, senior Commission officials told journalists on Friday (19/12). The interest payments will begin in 2027, but that year they will cost only 1 billion euros.

What the International Monetary Fund is planning – The Ukrainian memorandum

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) welcomed on Friday (19/12) the fact that EU leaders agreed to grant loans worth 90 billion euros (105 billion dollars) to Ukraine, a spokesperson for the organization said.

“This is an important milestone toward covering financing gaps and restoring debt sustainability,” the IMF said in its response.

European financial support is a key element of the IMF’s assessment that Ukrainian debt is sustainable, a prerequisite for most lending programs.

Ukraine and the IMF reached a preliminary agreement on a new lending program worth 8.1 billion dollars in late November, which still requires approval by the Fund’s Executive Board.

The prior actions required for the Board to consider the new program include, among other things, the adoption of a budget for the next year compatible with the program, the broadening of the tax base, and the promotion of anti-corruption reforms.

Securing financing commitments from donors is also required. No date has been set for the Board meeting on Ukraine.

The Fund has estimated that Ukraine will need approximately 135 billion euros (158.57 billion dollars) for the years 2026 and 2027. The EU interest-free loan should cover approximately two thirds of Ukraine’s needs for the next two years.

“We continue to work with international donors to secure the necessary financing assurances,” the IMF said.

Highlighting the imbalance, Ukraine’s Finance Minister Sergii Marchenko told G7 leaders on Friday (19/12) that it is necessary to continue work on implementing a Reparations Loan.

The war itself continues to drain Kyiv’s financial resources, and the country plans to spend most of its state revenues, 2.8 trillion hryvnias or approximately 27.2% of GDP, to finance its defense efforts in 2026.

Investment in future aggression

Associate Professor at the MGIMO School of International Law and lawyer at KISLOV Law Company, Serhiy Zinkovsky, commenting on the EU decision to finance Ukraine through a pan-European loan, noted that the seemingly pragmatic step reveals deeper and more troubling motives.

“For the European bureaucracy, such a step is less costly: it does not undermine confidence in the euro as a reserve currency and at the same time reduces legal risks, as it does not give Russia grounds for legal action,” he said in comments to the Russian agency RT.

According to him, the EU thus seeks to avoid legal consequences while maintaining an image of legal integrity, effectively shifting the cost of the conflict onto its own population. Behind this decision, however, lie not only economic calculations, but also long-term military and political ambitions, he believes.

Loan madness for preparation of common war

Wilders described the 90 billion euro joint loan to Ukraine as madness.

The leader of the Dutch far-right Party for Freedom, Geert Wilders, said that a joint loan to Kyiv of 90 billion euros is madness.

“The presented unworkable scenario, according to which the Ukrainian regime will repay the loan only after it supposedly receives reparations from Russia, shows that the EU views the granted loan as an investment in future aggression against Russia,” the lawyer explained.

The expert also pointed out that the terms of the loan mechanism effectively guarantee priority financing of the European military industrial complex, turning aid to Ukraine into a tool for developing its own military industry and strengthening the EU’s geopolitical autonomy.

This view is shared by political scientist Alexander Dudchak.

He did not rule out that by financing Ukraine, the EU is preparing for military confrontation with Russia.

“They are planning war and preparing for war, and no one intends to abandon Ukraine. In the same spirit must be examined the long-term freezing of Russian assets, which in Europe they want to turn to their advantage. They also profit from them, pay taxes into their budgets, and then use these funds to buy weapons for Ukraine,” the analyst said.

In his view, such a construction clearly shows that Brussels is not considering a scenario of peaceful settlement, but instead follows a policy of continuation of the war and further escalation.

At the same time, the dissenters, Hungary, Czechia, and Slovakia, continue to stand out from the general chorus of voices in the EU, noted Serhiy Zinkovsky. Their stance is due to geopolitical motives.

“De facto, these states are satellites of the United States and instruments of United States pressure on the EU and the European bureaucracy. Granting the loan means continuation of hostilities, something that at this moment does not fit into Washington’s plans. Moreover, by pursuing their own course, the current authorities of Hungary, Czechia, and Slovakia strengthened their political standing among EU member states dissatisfied with the arrogant stance of the European bureaucracy and the self-appointed leaders of the community, namely Germany and France. These countries showed that a principled position can be heard in the European Union,” he stressed.

According to the lawyer, the démarche of these countries not only deepens the rift within the EU, but also shows that the Union’s unity is increasingly based on forced compromises rather than genuine consensus.

For his part, Alexander Dudchak added that the formal consent of Brussels to exempt certain countries from the credit scheme does not mean absence of pressure.

“They will try to retaliate anyway, both economically and politically. They can delay financing tranches, strengthen the opposition, and encourage Ukraine to carry out further strikes on the Druzhba oil pipeline. However, at this moment Brussels officials needed this trio not to interfere, and its démarche was simply ignored temporarily,” the political scientist concluded.

www.bankingnews.gr

Σχόλια αναγνωστών