Written by Dr. Thodoris Deligiannis

Based on trite patterns of thought, our era is incomprehensible.

Macroeconomic analysis models must be adapted to the new conditions if we wish to have a compass regarding the deep transformations in the economic sphere.

This means that we must identify the new terms that describe geopolitical developments and then see how they are transformed, geoeconomics comes to the forefront.

What does Donald Trump’s phrase that International Law is not needed mean. Is it merely a crisis of imperial grandeur or does it reflect a broader reality.

Everyone has suspected it, as is evident from media headlines and analyses, but what is taking shape is a kind of “Trump Doctrine”, a contemporary extension of the old Monroe Doctrine proposed by the American president in 1823.

At a practical level, this is the explicit reassessment by the United States of the Western Hemisphere as a zone of the highest strategic priority, combined with an aggressive negotiating stance in trade, energy, minerals, technology, and security.

This is not a theoretical perception of international relations.

It translates into significant decisions, noise, announcements, and simultaneous moves on multiple chessboards.

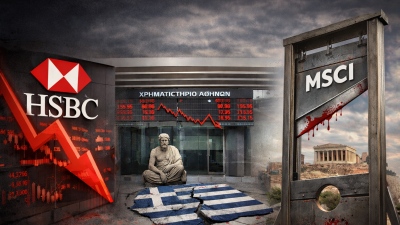

And here is what many have not yet digested: macroeconomic analysis based exclusively on charts, on the DXY dollar index, on the bond yield curve, and on monetary narratives is no longer sufficient.

Not because these elements have ceased to matter, but because in this new era geopolitics is not the background of developments in the economy, it is now the driving lever of developments.

And when geopolitics becomes the engine of developments, the impact on markets tends to be transformed, it concerns entire sectors, it is faster in terms of its consequences, it is more asymmetric and often more violent.

When the world returns to the logic of the state as the basic political unit (statecraft), each individual country or bloc begins to think as a state, not as a participant in a cooperative globalization, a zero-sum game, as under the regime of the liberal order which operated on the basis of rules.

The new rules

From the planetary logic of horizontal economic integration we move to the demands of economic sovereignty governed by the following logic: what is my advantage, what are my vulnerabilities, which dependencies must I stop, in raw materials or in supply chains, which resources must I secure and what cost am I willing to pay for it.

As a consequence, markets stop pricing a smooth, homogeneous story of “global growth” and begin to react to infarctions in supply chains, routes of goods, sanctions regimes, strategic reserves of critical goods, industrial complexes, and above all targeted fiscal spending.

That is why it is observed, almost as an immediate reflex, that investors rush into goods such as copper, silver, gold, and other critical minerals, trying to anticipate where the next wave of public spending will be directed.

Not only in the United States, but also in China and Europe, because everyone operates on the basis of domestic politics and the nation as the sovereign economic unit.

Globalization, as we knew it, has ended

What now exists is a reorganization into spheres of influence, with costly excess redundancy and productive capacity, with the gradual lifting of the division of labor that globalization brought, and “war-like” competition for inputs or raw materials.

The incident with Venezuela and the arrest of Nicolas Maduro appears here as the move of a pawn in a chess game, not as an isolated incident.

Already the tectonic plates of geopolitics moved with the special military operation of Vladimir Putin in Ukraine which began in February 2022, and the long-term result it had is that the rules of the game were rewritten with the direct challenge to the rules-based liberal order.

When you have a country with significant reserves of oil and gold, and when that country moves in the orbit of competing axes, the dispute does not concern “oil priced in dollars”.

The dispute concerns reintegration into or exclusion from the dominant financial system, control of flows, sanctions, custodianship of financial products, who finances investments, who insures investment projects, who clears transactions, and in which currency.

The competing blocs are already largely formed: the United States and the Anglo-Saxon world, and our guide in reading a world that will be divided into geopolitical zones or “empires” will be the theory of Carl Schmitt.

The concept of the Greater Space (Großraum)

The term Großraum (Greater Space) was formulated by the prominent German National Socialist jurist, antisemite, and political theorist of the Interwar period, Carl Schmitt, in 1939.

In 1941, the first issue of the National Socialist magazine “20th Century” is published in Shanghai, China, then under Japanese occupation.

There, Schmitt publishes the article “Großraum und Reich” (Greater Space and Empire), a summary of an earlier study of his.

In this text he attempts to deconstruct the western, liberal order in international law and international politics.

In contrast to what he considered the obsolete theory of the sovereign state and the global political conditions imposed through its sea power by Great Britain, he proposes the introduction into legal terminology of the concepts of the Greater Space and the Empire.

Schmitt believed that the international order is moving, or returning, meaning the shaping of geopolitical space in the Middle Ages, to forms of formation of geopolitical entities that transcend the territory of the state.

The theory of Großraum is as follows: a sovereign power, Empire (Reich), prevails within a larger territorial space, the Großraum, within which it essentially acts as a hegemonic power.

This larger space must be characterized by sufficient cultural homogeneity so as to allow the “political idea” of the Reich to unify.

The hegemonic state is responsible both for choosing the ideological basis of the Großraum, the dominant political idea, at this point the German jurist inspires the Russian philosopher Alexander Dugin, who speaks of a broad Russian cultural territory, and also possesses the power to decide on the external orientation of the Greater Space as a whole.

The Greater Space is intended to shape geopolitical spaces, replacing the classic nation-state, which Schmitt considered increasingly inadequate to represent a specific spatial reality of the industrial era.

We can imagine how this applies exponentially today in an era of planetary integration of economic structures.

This Großraum-based order was intended to replace the principle of equality of sovereign states that had prevailed with the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, which with the concept of state sovereignty put an end to the Religious Wars, the treaty in question marked the end of the extremely destructive Thirty Years’ War (1618 - 1648) between Roman Catholics and Protestants, and the abolition of the medieval papal-imperial ordo rerum that had defined western history for 8 centuries.

The treaty in question is replaced with a complex set of hierarchies between hegemonic and subordinate states in different macro-regions or geopolitical spaces of the earth, thus offsetting what he considered a flaw of liberal or Marxist-Leninist ideologies which claimed to have a universal character.

The element of racial superiority was not essential to Schmitt’s Großraum, in contrast to the concept of Lebensraum (living space), but it could be easily adapted.

The concept legitimizes aggressive policies against non-homogeneous states and minorities within Europe, framing them in a legalistic narrative that supported German hegemony.

The influence of the Monroe Doctrine

Schmitt’s ideas were not entirely new, as they drew inspiration from the Monroe Doctrine to show how a Greater Space could function as a sphere free from external interventions, establishing a new legal order based on regional hegemony rather than universal principles, as required by liberal law.

According to Schmitt, the Monroe Doctrine had three significant consequences in international law: the American states were considered independent, colonialism and intervention in their territories by non-American powers were prohibited, while at the same time implying mutual non-intervention of American powers outside America.

The Monroe Doctrine was not based on a treaty between legal subjects, its meaning was defined, interpreted, and applied exclusively by its political subject, namely the United States.

The relationship with spheres of influence

Schmitt’s conception of the Großraum is also close to the concept of spheres of influence.

Both concepts concern the geopolitical exercise of power, but they differ significantly in terms of their implications: the Großraum refers to a structured geopolitical order dominated by a great power in a defined area, whereas the sphere of influence describes an area where a state or organization exercises significant cultural, economic, or political influence without necessarily direct control.

Spheres of influence are more fluid and less standardized, while like the Greater Space they are characterized by legal fluidity, they do not always correspond to formal treaties or alliances and may be expressed through informal arrangements that recognize the sovereignty of one state over another without full annexation.

Incidentally, at this point it is easy to understand how the discussion in Europe, for example about “security guarantees” in Ukraine, is in fact placed outside the new framework.

Schmitt’s theory was not merely academic, but a militant formulation and justification of a new order of things that would replace the declining, then and now, jus publicum Europaeum, the European legal order.

Schmitt, a vehement opponent of legal positivism, sought to exercise a formative approach to international law, seeing the Greater Space as an attempt to identify the birth pangs of a new order.

He observes that four frameworks of legal relations emerge: between Großraume/Greater Spaces, between leading Reiche/Empires, between peoples within the Großraum, and between peoples of different Großraume.

Of course, these thoughts are made within the framework of the 20th century, and specifically the Second World War, outlining the then global distribution of power among the United States, Great Britain, Germany, Italy, Japan, and the Soviet Union.

They are the intellectual, ideological, and legal tools for securing the expansion and claim of the hegemonic position of National Socialist Germany.

At the same time, the described situations strikingly resemble the geopolitical condition of the European Middle Ages, and particularly the spaces and interactions of Eastern and Western Christianity.

The contemporary formation of a post-liberal order

There are clear affinities between Schmitt’s theories and today’s international legal order.

The United Nations Charter and subsequent practice have favored the regional character of alliances and, despite initial opposition to spheres of influence, have ended up unintentionally implementing some of Schmitt’s ideas.

This is evident through the creation of regional treaties such as NATO, the Warsaw Pact, the African Union, and through Article 52 of the Charter, which gives purpose to regional arrangements or organizations within the framework of international peace and security.

Some argue that the horizontal perception of the international legal order is anachronistic, as the United States and the rising China already possess zones of influence that transcend their national borders.

The Großraum model has therefore been detached from Nazi legal theory and is now associated with multipolarity and regionalism in the international order.

The forces of transformation today

Within the context of the retreat of the liberal order, some powerful states, “modern candidates for Reich/Empires”, according to Schmitt, have recently expanded territory and influence: Trump’s recent operation in Venezuela and statements about vital United States interests in the Panama Canal and Greenland, Putin’s doctrine for the war in Ukraine in the form of a historical justification, land and maritime expansions of China at the expense of smaller neighbors, the continuous expansion of Israel after the Six-Day War of 1967 (West Bank, Golan Heights, Gaza Strip), and Tayyip Erdogan’s statement that Turkey cannot be confined to its borders (Syria, Libya, Somalia).

Some analysts have drawn parallels with Schmittian theories of geopolitical space.

Schmitt recorded a revolution in the perception of space analogous to that of the 16th century and to what is taking place in the 21st century.

The current wave of geopolitical upheavals and the recovery of economic sovereignty by powerful states that are freeing themselves from the liberal conception of the international order could herald a similar revolution.

It is doubtful whether Donald Trump himself has read Carl Schmitt.

The billionaire of big tech and close advisor to Trump, Peter Thiel, on the other hand, has repeatedly referred to the state theorist Schmitt in interviews and applies his theory in his thinking.

What is certain is that this theory is changing the world as we knew it.

The recognition of political realities that at times transcend law shapes geopolitical developments and the multiple levels of war that will be waged for the formation of future Greater Spaces, the existence of which has begun to be foreshadowed.

www.bankingnews.gr

Σχόλια αναγνωστών